Back to Learn page

Back to Learn page

What is Securities Lending?

In any market, investors are always looking for the next edge. If I were a pinstripe-suit-wearing Wharton graduate, I’d say that investors are looking for “new ways to generate alpha” (or ways to outperform the market).

Whether it’s complicated options trading, long-term buy and hold strategies, or finding the next great company no one else has heard of, many investors look for ways to increase returns consistently year-over-year. However, there’s one often overlooked method that might be right in front of you: securities lending.

Defining Securities Lending

So… what is securities lending? Strictly speaking, it’s when a firm (often a brokerage firm) loans out the securities in its portfolio (like stocks, bonds, ETFs, etc.) to other investors. In exchange for loaning these securities to them, the borrower stakes collateral to the lender (this can come in the form of an upfront cash payment, other securities, or something else), and pays an interest rate fee over the course of the borrowing term.

What is Short Selling?

Before we get into the nitty gritty of securities lending, let’s quickly chat about the other side of the transaction. Many investors borrow securities in order to engage in something called short selling. While it might take a pinstripe suit and a Wharton degree to truly master short selling, here’s a metaphor to help you understand the fundamentals:

Let’s say that the new iPhone is releasing in a week, and you think there will be a surplus of used iPhones as people cash in their old models to buy the new one. You have a theory that this will lower the value of each unit in the immediate future. You know a friend with a spare iPhone, so you offer to borrow it from him for a fee. You give him a small collateral, and pay him 10 cents per day in fees for his troubles. You immediately turn around and sell that iPhone to someone else for $100. Now you have $100 in cash, but you still owe your friend one old iPhone. Well, your prediction comes true and used iPhones fall to $50 in value when the new one is released a week later. You now buy a used iPhone back for $50, then give it back to your friend that originally lent you the first one. You now owe nothing to anyone, and you walk away with $50 in cash, minus the fee you paid to borrow your friend’s phone.

That, my friend, is the essence of short selling, except investors do this with stocks and other securities instead of iPhones. Investors who engage in short selling are betting that a security will fall in value, so they borrow the securities, sell them, and hope to buy them back at a cheaper price so they can return them and pocket the difference as profit.

Why is Securities Lending a Thing?

Now, back to securities lending. Although borrowers can make money through short selling, the firms that lend out securities get paid their lending fee and get their securities returned in the end. This means that securities lending could be one way for firms to turn a profit if they have a large number of securities that would otherwise be sitting in their portfolio untouched long term.

The act of investors trying to maximize their investments is nothing new, and neither is securities lending. The practice has been around for decades. In the 1920s-1930s, the New York Stock Exchange even had a public “loan post” that served as an early in-person securities lending stand.

Securities lending became more formalized in the 1960’s, when traders in London began to take advantage of new runs on investors pouring into short sales. From there, the toothpaste was out of the tube. Securities lending, as a business, was in full swing. And by “full swing,” I mean that RBC estimated in 2020 that there is over $30 trillion in securities enrolled in lending programs around the world.

Why Lend Your Securities?

Well, as we mentioned above, investors are looking for that extra revenue in their portfolios. That can be generated by lending your securities to someone that is looking to execute a short sale, as described in the iPhone example above. Additionally, thanks to fixed fee rates dependent on security demand, it’s potentially one way to drive a bit of extra cash.

If you’re a big bank or financial body, however, then securities lending takes on a bit of a new meaning: liquidity. Take for example the European Central Bank. Since 2015, the ECB has been purchasing billions in public bonds, that they then lend out to other investors at a fixed fee of 5 basis points (aka 0.05%) for securities, or a 20 basis point (0.20%) discount rate for collateralized cash. Essentially, this accomplishes two missions for the ECB: 1) The ECB becomes a market maker for public bonds; and 2) It’s able to drive additional revenue to the balance sheet through lending fees. In this example, the ECB has access to cash that would be otherwise tied up in bonds.

The Downsides to Securities Lending

In the case of the individual lender, there are some downsides to securities lending. As with all investing, lending securities involves risk. There’s a risk that the borrower may go bankrupt. In that case, the lending broker is on the hook to return the shares. There’s also a chance that the lender may miss out on price fluctuations while the securities are loaned out. If you loan your shares out at $10 per share, then they jump to $20 while they’re loaned out, then drop back to $12 when you get them back, then you’ve missed out on some significant unrealized gains.

It’s worth noting that when stocks are loaned out, the title and ownership of these stocks are transferred to the borrower, meaning that the lender doesn’t have control of the shares until they are given back. While the obvious result of this would be that the lender can’t trade stocks that are loaned out, it also means that the lender can’t do other things with these shares on loan — like use them to participate in shareholder votes.

Whoever owns the shares on the record date is the one able to vote those shares. This means in some cases, the borrower could get the right to vote if they hold the shares on the record date. There have been some instances where institutional investors borrow shares to swing votes. Separately, if the borrower participates in a short sale and sells the shares in order to buy them back later, the investor who bought the shares from the borrower gets the right to vote. Either way, the votes follow the shares and the original owner won’t be able to vote with shares that are loaned out.

Another downside is that if loaned shares are used for short selling, it puts downward pressure on the stock price of the shares being loaned. Essentially, this means the borrower is betting against the lender that could be looking to hold these shares for the long term. The lender could see the value of their securities depreciate.

How Do I Lend My Securities?

So now you know that brokerage firms can lend out securities, but how do you, a retail investor, lend your shares? The harsh truth is you might be lending them out without even knowing. Brokerages have the ability to lend out shares to investors, which sometimes involves lending out shares that are in the portfolios of their retail investor clients. Meaning that your brokerage may have the ability to lend out your shares. While some brokerages advertise that they allow their users to enroll in securities lending, some retail investors might not know whether they are lending their stocks or not. How come?

Well, remember when you signed up for your brokerage account and there was that thing you scrolled to the bottom of and pressed “I Accept” so you could get to your YOLO options trades quicker? Well, that’s called the “Terms and Conditions” and some brokerages include your consent to lend securities within that document. If you’re wondering whether your broker has the ability to lend your shares, look for the term “fully paid securities lending” in the Terms and Conditions you signed. The unfortunate truth is, you may have given your consent unknowingly in that document.

Brokerages are able to do this with retail investor clients who own margin accounts with them, and your consent for this might be located in the hypothecation agreement you have to sign when opening a margin account. Between the Terms and Conditions, hypothecation agreement, or your expressed consent form, you may have yelled consent in a few different ways to your brokerage of choice (if they opt to do securities lending).

Brokerages make money when they lend securities. Sometimes they pass some of that profit to the individual investors who are getting their securities lent. But even if you’re getting paid to lend out your securities, it’s worth weighing the downsides of securities lending — like losing access to your shares, not being able to use them to vote, and having short sellers bet against you — in order to determine if it’s worth the price.

If you do discover that your brokerage is lending your securities (and essentially your shareholder vote) and it’s not something you’re comfortable with, the next step could be switching to a brokerage that doesn’t lend securities. If you are comfortable with it, it could be worth doing some research to see which brokerages pay the best rates for lending out your securities. Either way, they are your shares, so what you choose to do with them should be up to you.

The views expressed are those of the author at the time of writing, are not necessarily those of the firm as a whole and may be subject to change. The information contained in this advertisement is for informational purposes and should not be regarded as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any. It does not constitute a recommendation or consider the particular investment objectives, financial conditions, or needs of specific investors. Investing involves risk, including the loss of principal. Past performance is not indicative or a guarantee of future performance. We do not provide tax, accounting, or legal advice to our clients, and all investors are advised to consult with their tax, accounting, or legal advisers regarding any potential investment. The information and any opinions contained in this advertisement have been obtained from sources that we consider reliable, but we do not represent such information and opinions are accurate or complete, and thus should not be relied upon as such. This is particularly true during periods of rapidly changing market conditions. Fennel refers to Fennel Markets, Inc., and Fennel Financials LLC. Securities offered through Fennel Financials LLC, member FINRA/SIPC.

Expand your knowledge further

Here's what you should know about Fennel's real-time news feature.

Screening is one way to incorporate ESG into your portfolio.

How a company acts affects more than just its product or its bottom line, it affects the world around it — for better or for worse

In any market, investors are always looking for the next edge

You may already know that owning stock means owning a portion of a specific company

Beta, enterprise value, expense ratio ... what does it all mean? Here are definitions for the terms you'll see in the Fennel app.

Some brokerages use payment for order flow to generate extra revenue, but at what cost?

Think of the Fennel ESG wheel as an ESG report card.

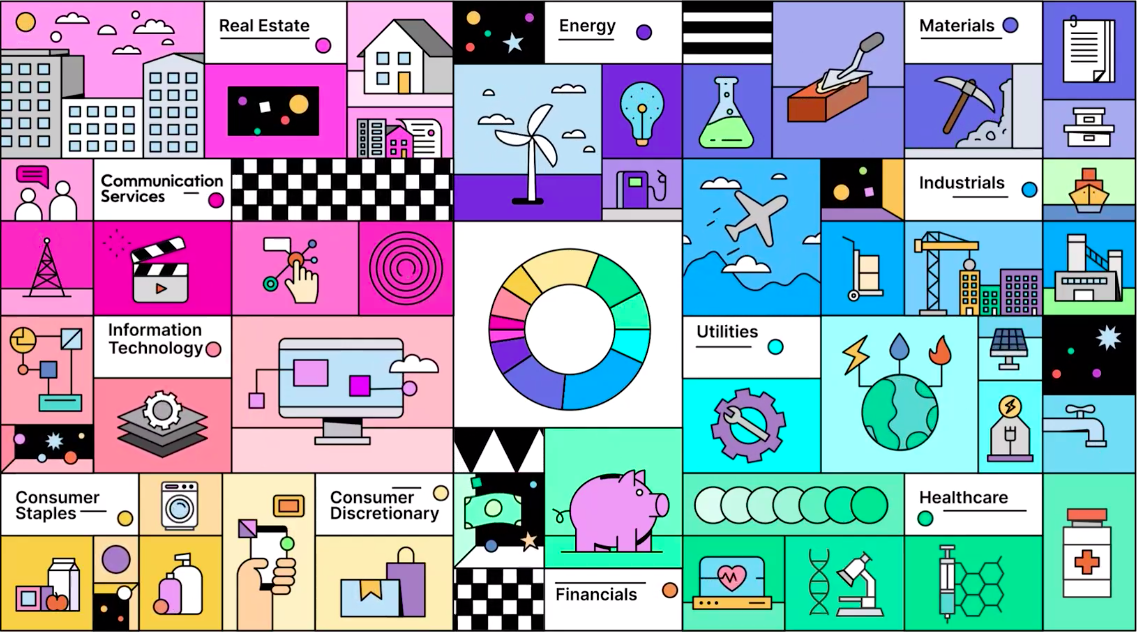

Sectors can help you understand the industry of the companies you invest in.

If you've ever found yourself nodding along to conversations about investing while secretly wondering if everyone else in the room is speaking a different language, you're not alone.

Take back the power of your investment