Back to Learn page

Back to Learn page

What Is Payment For Order Flow?

Some brokerages use payment for order flow to generate extra revenue, but at what cost?

While the digital age revolutionized most of the investing process for retail investors, one legacy feature that held on for dear life was commissions. Traditionally, brokerages used commissions to charge consumers for access to the markets. Even as more brokers were conducting business online, popular brokerages were still charging $5, $10, even $20 per trade. That is, until a handful of young tech-forward brokerages came along with a new business model that changed the industry: commission-free trading.

But how do these brokerages still manage to make money, despite not charging a commission?

That’s where a revenue stream known as “payment for order flow” (PFOF) comes in. By making money through payment for order flow, brokerages can get away with not charging commissions. But this practice isn’t without controversy. In fact, the SEC determined that Robinhood’s use of PFOF from 2015-2018 “misled customers” — resulting in customers paying higher prices to execute trades.

So what exactly is PFOF, and why has it suddenly become a topic of conversation in investing circles?

What is Payment for Order Flow?

Strictly speaking, payment for order flow involves a market maker paying a brokerage for the right to execute their trades. As dry as that is, it’s pretty important to understand for the average retail investor.

The concept of PFOF actually isn’t new. The practice dates back a few decades and was even used by Bernie Madoff (yes, that same Bernie Madoff) back in 1991. PFOF was pioneered as another way for large trading funds, known as “market makers,” to generate business with a specific brokerage.

The process is actually pretty straightforward: the market maker approaches a brokerage to be their primary trading house for buying and selling securities. The market maker, in return for the business, pays the brokerage fractions of a cent for each share they buy or sell. While that doesn’t sound like much, the volume of shares trading hands per day means that this payment to the brokerage can be hundreds of millions of dollars.

While the brokerage is getting paid through the nose by the market maker, the market maker is benefiting on the other side by taking advantage of the difference between the buy and sell prices of securities. This difference is called the “bid-ask spread” and can be anywhere from fractions of a cent to several cents per share. Since the market maker handles both sides of the buy-sell transaction, they get to pocket the difference. Theoretically, the market maker is making a return on their investment on top of what they’re paying the brokerage, which is what makes PFOF appealing to both brokerages and market makers.

Arguments For PFOF

PFOF, in general discourse, is viewed in a …not so positive light. In fact, PFOF is illegal in the UK and Canada. However, there are some valid arguments in adopting the practice.

The first is one we’ve already touched on: PFOF brings in additional revenue for the broker, which can allow the broker to eliminate commissions on trades. For Robinhood, this model generates a whopping 75% of their total revenue, which allows them to avoid charging commissions to retail investors. Zero commissions is a pretty enticing thing for the end user, who doesn't have to pay hefty fees every time they want to execute a trade.

The second argument in favor of PFOF is that it helps to generate liquidity in the market. Like toilet paper in 2020, you can’t buy a stock if the inventory is unavailable. By acting as a middleman, market makers argue that they provide the necessary liquidity to keep shares moving. This is especially true in the options market, where high volumes of contracts change hands every minute.

Arguments Against PFOF

Detractors of the PFOF model have some points of their own. Namely, that the routing of orders to a specific market maker creates a conflict of interest in the execution of the trade. This could lead to investors not getting the best prices on their trades, since the buying and selling is running through the same market maker, and that market maker is looking to make money on the spread. It could also create issues if the market maker is put in a tough position, like what happened in early 2021.

PFOF In The 2021 Memestock Trade

Nowhere was the PFOF conflict of interest more apparent than in the memestock revolution of 2021. For those of you that lived in a Faraday Cage at this time, members of online forums like r/WallStreetBets banded together to buy shares of GameStop, AMC Theaters, and other nostalgic companies, in an attempt to cause a historic short squeeze that damaged short holders. It even drove one hedge fund that shorted GameStop out of business.

It was at this time that a few of the brokerages favored by the memestock traders, turned off the buy function for some of these stocks. This deeply upset traders, and many accused the market makers of telling brokers to turn off the buy function so the market makers could minimize the damage against their short positions — thus the conflict of interest.

The public outrage even led to some of the more high-profile figures being forced to testify in front of Congress about the issue. Both Robinhood CEO, Vlad Tenev, and Citadel CEO, Ken Griffin, had to testify, but not too much happened as a result. Even though over 30 class actions lawsuits were filed against Robinhood, several of these claims are being dismissed by federal courts.

But the spectacle put a spotlight on PFOF that has yet to go away. Congress also held a second hearing on PFOF, which eventually led new SEC Chairman, Gary Gensler, to further discuss “the future” of PFOF revenue — leading some to wonder if PFOF will be made illegal. Then in June 2022, over a year after the memestock episode, Gensler made it seem like PFOF’s days may be numbered.

The future of PFOF is up in the air, but at the end of the day, interacting with PFOF is not a necessity of online investing. While some brokerages partake in payment for order flow, others do not. Each person will view PFOF differently, so it’s up to you to do your own research and determine which platform is right for you.

∙ ∙ ∙

The views expressed are those of the author at the time of writing, are not necessarily those of the firm as a whole and may be subject to change. The information contained in this advertisement is for informational purposes and should not be regarded as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any. It does not constitute a recommendation or consider the particular investment objectives, financial conditions, or needs of specific investors. Investing involves risk, including the loss of principal. Past performance is not indicative or a guarantee of future performance. We do not provide tax, accounting, or legal advice to our clients, and all investors are advised to consult with their tax, accounting, or legal advisers regarding any potential investment. The information and any opinions contained in this advertisement have been obtained from sources that we consider reliable, but we do not represent such information and opinions are accurate or complete, and thus should not be relied upon as such. This is particularly true during periods of rapidly changing market conditions. Securities offered through Fennel Financials, LLC. Member FINRA SIPC.

Expand your knowledge further

You may already know that owning stock means owning a portion of a specific company

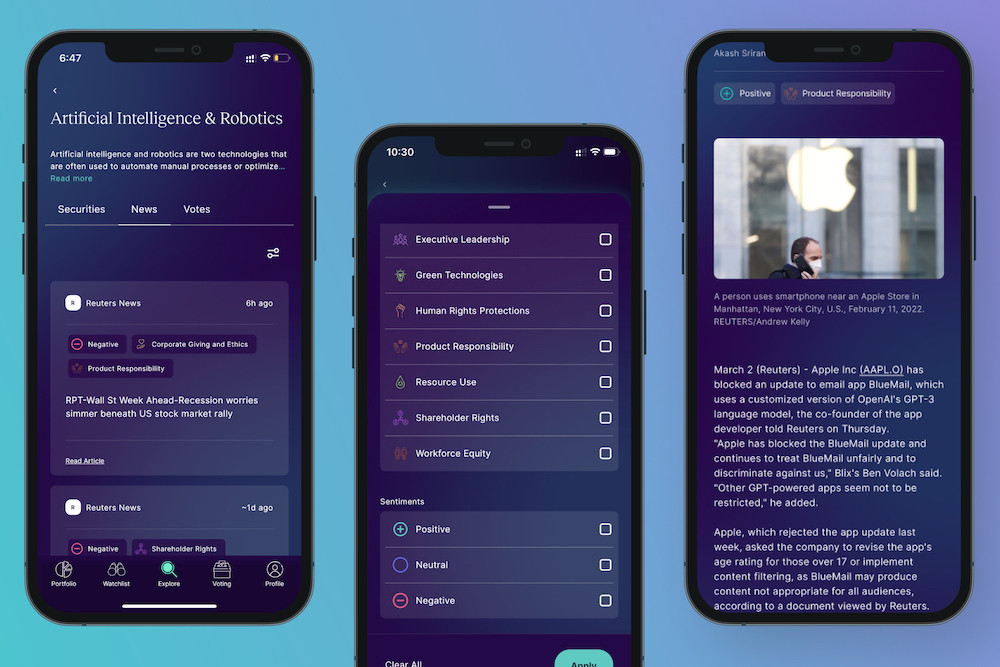

Here's what you should know about Fennel's real-time news feature.

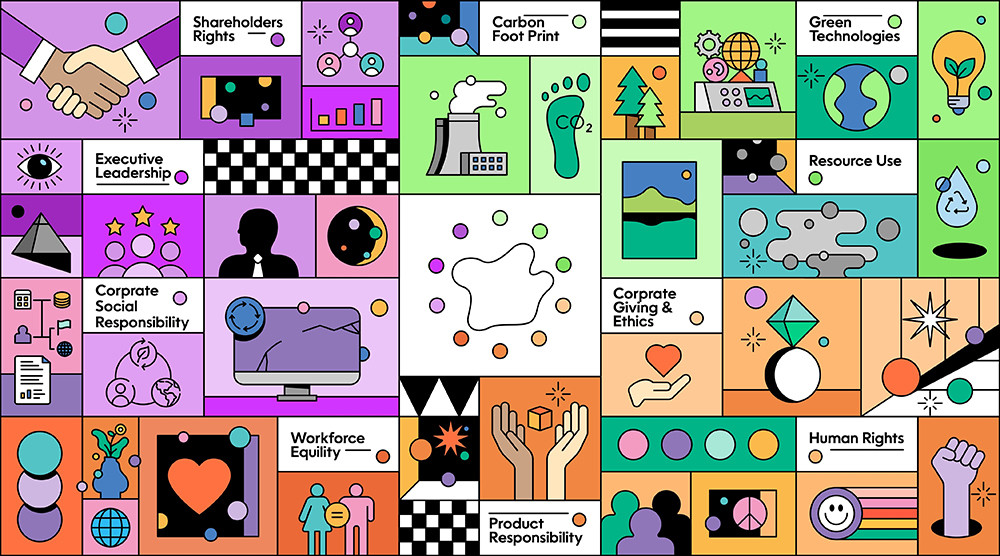

How a company acts affects more than just its product or its bottom line, it affects the world around it — for better or for worse

Some brokerages use payment for order flow to generate extra revenue, but at what cost?

Fennel is giving you even more control over your portfolio by letting you decide how your orders get routed.

If you've ever found yourself nodding along to conversations about investing while secretly wondering if everyone else in the room is speaking a different language, you're not alone.

Sectors can help you understand the industry of the companies you invest in.

Screening is one way to incorporate ESG into your portfolio.

Beta, enterprise value, expense ratio ... what does it all mean? Here are definitions for the terms you'll see in the Fennel app.

Think of the Fennel ESG wheel as an ESG report card.

Take back the power of your investment